More Heapsort in Cython

This post/notebook is the follow-up to a recent one : Heapsort with Numba and Cython, where we implemented heapsort in Python/Numba and Cython and compared the execution time with NumPy heapsort. However, heapsort in NumPy is written in C++ (wrapped in Python) and not exactly the same implementation as the one we used in the previous post. So in the following, we present two different heapsort implementations translated into Cython, which are a little bit more refined than the previous one:

- the first one (

Cython_1) is taken from the book Numerical recipes in C [1] - the second one (

Cython_2) is taken from NumPy source code: heapsort.cpp

In both implementations, indices are 1-based and left bitwise shift (<<) and right bitwise shift (>>) operators are used. In order to use 1-based indices with NumPy arrays, we add an extra element at the beginning:

def heapsort(A_in):

A = np.copy(A_in)

A = np.concatenate((np.array([np.nan]), A))

_heapsort(A)

return A[1:]

Also, the algorithms are implemented in a single function, and without recursion.

Imports

import gc

from time import perf_counter

import cython

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import perfplot

%load_ext cython

SD = 124 # random seed

rng = np.random.default_rng(SD) # random number generator

Float array creation

We still assume that we want to sort an NumPy array of 64-bit floating-point numbers between 0 and 1:

n = 10

A = rng.random(n, dtype=np.float64)

A

array([0.78525311, 0.78585936, 0.96913602, 0.74805977, 0.65555081,

0.93888454, 0.17861445, 0.58864721, 0.44279917, 0.34884712])

Cython_1

The authors of Numerical recipes in C [1] use a “corporate hierarchy metaphor”:

[…] a heap has every “supervisor” greater than or equal to its two “supervisees,” down through the levels of the hierarchy.

If you have managed to rearrange your array into an order that forms a heap, then sorting it is very easy: You pull off the “top of the heap,” which will be the largest element yet unsorted. Then you “promote” to the top of the heap its largest underling. Then you promote its largest underling, and so on. The process is like what happens (or is supposed to happen) in a large corporation when the chairman of the board retires. You then repeat the whole process by retiring the new chairman of the board.

Imagine that the corporation starts out with N/2 employees on the production line, but with no supervisors. Now a supervisor is hired to supervise two workers. If he is less capable than one of his workers, that one is promoted in his place, and he joins the production line. After supervisors are hired, then supervisors of supervisors are hired, and so on up the corporate ladder. Each employee is brought in at the top of the tree, but then immediately sifted down, with more capable workers promoted until their proper corporate level has been reached.

One execution of the Heapsort function represents the entire life-cycle of a giant corporation: N/2 workers are hired; N/2 potential supervisors are hired; there is a sifting up in the ranks, a sort of super Peter Principle: in due course, each of the original employees gets promoted to chairman of the board.

So we have two phases:

- hiring

- retirement-and-promotion

This is very similar to what we described in the previous post: a first step where we build the heap in a bottom-up approach, a second step where we keep on extracting the root until the heap is empty. Both steps rely on a sift-down process. However, we have here a single main loop for both phases.

%%cython -3 --compile-args=-Ofast

# cython: boundscheck=False, cdivision=True, initializedcheck=False, wraparound=False

import cython

import numpy as np

from cython import double, ssize_t

@cython.exceptval(check=False)

@cython.nogil

@cython.cfunc

def _heapsort_1(ra: double[::1]) -> cython.void:

i: ssize_t

ir: ssize_t

j: ssize_t

l: ssize_t

n: ssize_t = ra.shape[0] - 1

rra: double

if n < 2:

return

l = (n >> 1) + 1

ir = n

# The index l will be decremented from its initial value down to 1 during the “hiring” (heap

# creation) phase. Once it reaches 1, the index ir will be decremented from its initial value

# down to 1 during the “retirement-and-promotion” (heap selection) phase.

while 1:

if l > 1: # Still in hiring phase.

l -= 1

rra = ra[l]

else: # In retirement-and-promotion phase.

rra = ra[ir] # Clear a space at end of array.

ra[ir] = ra[1] # Retire the top of the heap into it.

ir -= 1

if ir == 1: # Done with the last promotion

ra[1] = rra # The least competent worker of all!

break

i = l # Whether in the hiring phase or promotion phase, we

j = l + l # here set up to sift down element rra to its proper level.

while j <= ir:

if (j < ir) & (ra[j] < ra[j + 1]): # Compare to the better underling.

j += 1

if rra < ra[j]: # Demote rra.

ra[i] = ra[j]

i = j

j = j << 1

else:

# j = ir + 1 # This is rra's level. Set j to terminate the sift-down.

break

ra[i] = rra # Put rra into its slot.

@cython.ccall

def heapsort_cython_1(A_in):

A = np.copy(A_in)

A = np.concatenate((np.array([np.nan]), A))

_heapsort_1(A)

return A[1:]

A_1 = heapsort_cython_1(A)

A_1

array([0.17861445, 0.34884712, 0.44279917, 0.58864721, 0.65555081,

0.74805977, 0.78525311, 0.78585936, 0.93888454, 0.96913602])

np.testing.assert_array_equal(A_1, np.sort(A))

Cython_2

This is a straight translation of NumPy Source code from C++ to Cython. Here is what we can read in the source code about its origin:

* These sorting functions are copied almost directly from numarray

* with a few modifications (complex comparisons compare the imaginary

* part if the real parts are equal, for example), and the names

* are changed.

*

* The original sorting code is due to Charles R. Harris who wrote

* it for numarray.

This time we have two distinct loops in the _heapsort_2() function. But this is very similar to the code above (Cython_1).

%%cython -3 --compile-args=-Ofast

# cython: boundscheck=False, cdivision=True, initializedcheck=False, wraparound=False

import cython

import numpy as np

from cython import double, ssize_t

@cython.exceptval(check=False)

@cython.nogil

@cython.cfunc

def _heapsort_2(a: double[::1]) -> cython.void:

i: ssize_t

j: ssize_t

l: ssize_t

n: ssize_t = a.shape[0] - 1

tmp: double

for l in range(n >> 1, 0, -1):

tmp = a[l]

i = l

j = l << 1

while j <= n:

if (j < n) & (a[j] < a[j + 1]):

j += 1

if tmp < a[j]:

a[i] = a[j]

i = j

j += j

else:

break

a[i] = tmp

while n > 1:

tmp = a[n]

a[n] = a[1]

n -= 1

i = 1

j = 2

while j <= n:

if (j < n) & (a[j] < a[j + 1]):

j += 1

if tmp < a[j]:

a[i] = a[j]

i = j

j += j

else:

break

a[i] = tmp

@cython.ccall

def heapsort_cython_2(A_in):

A = np.copy(A_in)

A = np.concatenate((np.array([np.nan]), A))

_heapsort_2(A)

return A[1:]

A_2 = heapsort_cython_2(A)

np.testing.assert_array_equal(A_2, np.sort(A))

Cython_3

For the sake of completeness, we also included the implementation from the previous post, with the same compiler directives as above:

%%cython -3 --compile-args=-Ofast

# cython: boundscheck=False, cdivision=True, initializedcheck=False, wraparound=False

import cython

import numpy as np

from cython import double, ssize_t

@cython.exceptval(check=False)

@cython.nogil

@cython.cfunc

def _max_heapify(A: double[::1], size: ssize_t, node_idx: ssize_t) -> cython.void:

largest: ssize_t = node_idx

left_child = 2 * node_idx + 1

right_child = 2 * (node_idx + 1)

if left_child < size and A[left_child] > A[largest]:

largest = left_child

if right_child < size and A[right_child] > A[largest]:

largest = right_child

if largest != node_idx:

A[node_idx], A[largest] = A[largest], A[node_idx]

_max_heapify(A, size, largest)

@cython.exceptval(check=False)

@cython.nogil

@cython.cfunc

def _heapsort_3(A: double[::1]) -> cython.void:

i: cython.int

size: ssize_t = len(A)

node_idx: ssize_t = size // 2 - 1

for i in range(node_idx, -1, -1):

_max_heapify(A, size, i)

for i in range(size - 1, 0, -1):

A[i], A[0] = A[0], A[i]

size -= 1

_max_heapify(A, size, 0)

@cython.ccall

def heapsort_cython_3(A_in):

A = np.copy(A_in)

_heapsort_3(A)

return A

A_3 = heapsort_cython_3(A)

np.testing.assert_array_equal(A_3, np.sort(A))

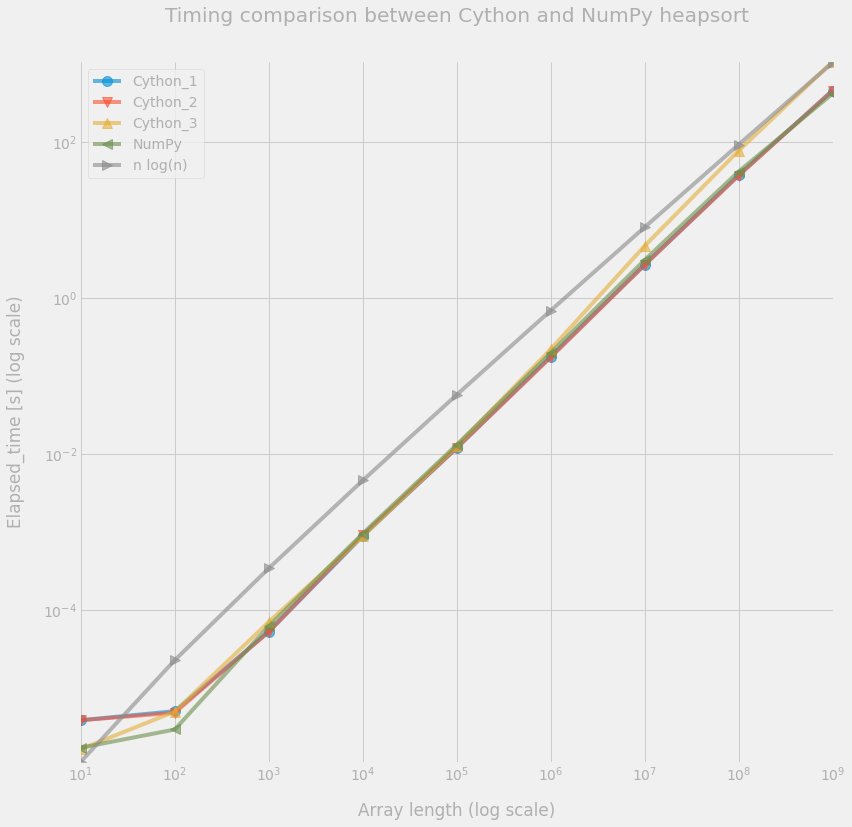

Performance comparison

Again, we compare the different versions against NumPy heapsort.

Perfplot

out = perfplot.bench(

setup=lambda n: rng.random(n, dtype=np.float64),

kernels=[

lambda A: heapsort_cython_1(A),

lambda A: heapsort_cython_2(A),

lambda A: heapsort_cython_3(A),

lambda A: np.sort(A, kind="heapsort"),

],

labels=["Cython_1", "Cython_2", "Cython_3", "NumPy"],

n_range=[10**k for k in range(1, 9)],

)

t_df = pd.DataFrame(out.timings_s.T, columns=out.labels, index=out.n_range)

t_df

| Cython_1 | Cython_2 | Cython_3 | NumPy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3.915e-06 | 3.908e-06 | 1.663e-06 | 1.737e-06 |

| 100 | 5.111e-06 | 4.890e-06 | 5.054e-06 | 2.977e-06 |

| 1000 | 5.326e-05 | 5.319e-05 | 7.090e-05 | 6.266e-05 |

| 10000 | 8.942e-04 | 9.227e-04 | 8.871e-04 | 9.634e-04 |

| 100000 | 1.202e-02 | 1.200e-02 | 1.272e-02 | 1.315e-02 |

| 1000000 | 1.779e-01 | 1.735e-01 | 2.202e-01 | 1.973e-01 |

| 10000000 | 2.666e+00 | 2.654e+00 | 4.641e+00 | 3.066e+00 |

| 100000000 | 3.740e+01 | 3.695e+01 | 7.699e+01 | 4.161e+01 |

So is seems that the Cython_1 and Cython_2 implementations achieve similar speed as NumPy’s version. However, the Cython_3 implementation is clearly slower when the array gets larger.

A Larger array

It is possible to run the algorithms on arrays with 1 billion elements, but without using perfplot for reasons related to memory capacity of the computer used to run the tests.

%%time

k = 9

A = rng.random(10**k, dtype=np.float64)

CPU times: user 4.05 s, sys: 679 ms, total: 4.72 s

Wall time: 4.72 s

timings = []

for _ in range(3):

start = perf_counter()

A_1 = heapsort_cython_1(A)

end = perf_counter()

elapsed_time = end - start

del A_1

_ = gc.collect()

timings.append(elapsed_time)

elapsed_time_1 = np.amin(timings)

timings = []

for _ in range(3):

start = perf_counter()

A_2 = heapsort_cython_2(A)

end = perf_counter()

elapsed_time = end - start

del A_2

_ = gc.collect()

timings.append(elapsed_time)

elapsed_time_2 = np.amin(timings)

timings = []

for _ in range(3):

start = perf_counter()

A_3 = heapsort_cython_3(A)

end = perf_counter()

elapsed_time = end - start

del A_3

_ = gc.collect()

timings.append(elapsed_time)

elapsed_time_3 = np.amin(timings)

timings = []

for _ in range(3):

start = perf_counter()

A_4 = np.sort(A, kind="heapsort")

end = perf_counter()

elapsed_time = end - start

del A_4

_ = gc.collect()

timings.append(elapsed_time)

elapsed_time_4 = np.amin(timings)

t_df = pd.concat(

[

t_df,

pd.DataFrame(

[[elapsed_time_1, elapsed_time_2, elapsed_time_3, elapsed_time_4]],

columns=out.labels,

index=[10**k],

),

],

axis=0,

)

t_df["n log(n)"] = 5.0e-8 * t_df.index * np.log(t_df.index)

Note that we also included the curve corresponding to $O(n\log n)$ in the following figure. However, we are aware that this is an asymptotic behavior on an abstract machine, but do not take into account some hardware effects, such has cache optimization.

t_df[['Cython_1', 'Cython_2', 'Cython_3', 'NumPy']]

| Cython_1 | Cython_2 | Cython_3 | NumPy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 3.915e-06 | 3.908e-06 | 1.663e-06 | 1.737e-06 |

| 100 | 5.111e-06 | 4.890e-06 | 5.054e-06 | 2.977e-06 |

| 1000 | 5.326e-05 | 5.319e-05 | 7.090e-05 | 6.266e-05 |

| 10000 | 8.942e-04 | 9.227e-04 | 8.871e-04 | 9.634e-04 |

| 100000 | 1.202e-02 | 1.200e-02 | 1.272e-02 | 1.315e-02 |

| 1000000 | 1.779e-01 | 1.735e-01 | 2.202e-01 | 1.973e-01 |

| 10000000 | 2.666e+00 | 2.654e+00 | 4.641e+00 | 3.066e+00 |

| 100000000 | 3.740e+01 | 3.695e+01 | 7.699e+01 | 4.161e+01 |

| 1000000000 | 4.547e+02 | 4.536e+02 | 1.059e+03 | 4.142e+02 |

ax = t_df.plot(loglog=True, figsize=(12, 12), ms=10, alpha=0.6)

markers = ("o", "v", "^", "<", ">", "s", "p", "P", "*", "h", "X", "D", ".")

for i, line in enumerate(ax.get_lines()):

marker = markers[i]

line.set_marker(marker)

plt.legend()

plt.grid("on")

_ = ax.set(

title="Timing comparison between Cython and NumPy heapsort",

xlabel="Array length (log scale)",

ylabel="Elapsed_time [s] (log scale)",

)

Reference

[1] William H. Press, Saul A. Teukolsky, William T. Vetterling, and Brian P. Flannery. 1992. Numerical recipes in C (2nd ed.): the art of scientific computing. Cambridge University Press, USA.