Enrich a digital terrain model

In this blog post, we will explore how to enrich a digital terrain model (DTM) using Python. We are going to use a DTM raster file of the region of Lyon, France, which was created in a previous post using data from the French National Geographic Institute (IGN): Lyon’s Digital Terrain Model with IGN Data. We will crop the DTM to a specific bounding box and enrich it with additional data using the efficient RichDEM package. Specifically, we will add slope and aspect data to the DTM, which can be used to analyze the steepness and orientation of the terrain.

Once we have enriched the DTM, we will save it to a new file and query it to extract data at specific locations. Finally, we will visualize hill shades with different azimuth and altitude angles.

Imports

import os

import contextily as cx

import earthpy.plot as ep

import earthpy.spatial as es

import geopandas as gpd

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

import numpy as np

import pandas as pd

import rasterio as rio

import richdem as rd

from rasterio.mask import mask

from shapely.geometry import Polygon

FIGSIZE = (12, 8)

INPUT_DTM_FP = "./lyon_dtm.tif" # input Digital Terrain Model (DTM) file path

CROPPED_DTM_FP = "./lyon_dem_cropped.tif" # cropped DTM file path

OUTPUT_DTM_FP = "./lyon_dem_enriched.tif" # enriched output DTM file path

System and package versions

We are operating on Python version 3.11.8 and running on a Linux x86_64 machine.

contextily : 1.6.0

earthpy : 0.9.4

geopandas : 0.14.3

matplotlib : 3.8.3

numpy : 1.26.4

rasterio : 1.3.9

richdem : 2.3.0

shapely : 2.0.3

First we need to load the data and crop the raster file with a bounding box expressed in the same Coordinate Reference System (CRS).

Crop the raster file to have an horizontal rectangle in EPSG:2154

Bounding box definition with longitude and latitude

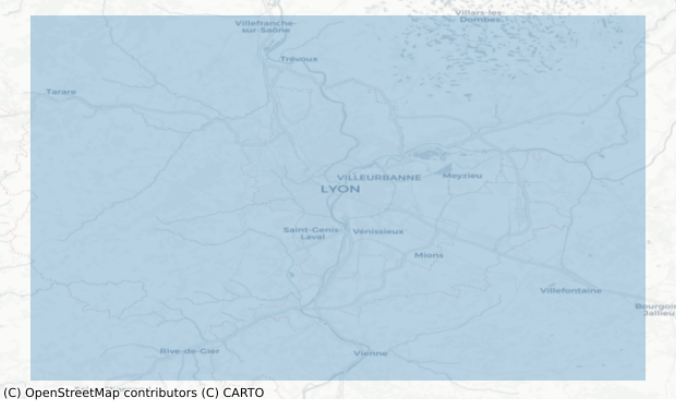

We define the bounding box coordinates in EPSG:4326 (WGS 84) and create a polygon from the points.

# Define bounding box coordinates in EPSG:4326

bbox = (4.393158, 45.487095, 5.262451, 46.004593)

# Define points to create a polygon

point1 = (bbox[0], bbox[1])

point2 = (bbox[0], bbox[3])

point3 = (bbox[2], bbox[3])

point4 = (bbox[2], bbox[1])

# Create a polygon from the points

polygon_4326 = Polygon([point1, point2, point3, point4])

# display the polygon with map tiles

bbox_gs = gpd.GeoSeries([polygon_4326], crs="EPSG:4326")

fig, ax = plt.subplots(1, figsize=(8, 8))

ax = bbox_gs.plot(alpha=0.3, ax=ax)

cx.add_basemap(ax, crs=bbox_gs.crs.to_string(), source=cx.providers.CartoDB.Positron)

ax.set_axis_off()

CRS change to a projected CRS

Now we change the CRS of the bounding box to a projected CRS in order to match the CRS of the raster file. A projected CRS is a coordinate system that uses a flat, two-dimensional surface to represent the three-dimensional surface of the Earth. This is in contrast to a geographic CRS, which uses angles (latitude and longitude) to represent locations on the Earth’s surface. The raster file we are working with in this blog post uses a projected CRS (EPSG:2154 - Lambert 93), which is a common CRS for maps of France.

The geometry.values[0] part of the code is used to display the geometry in its new CRS.

# change the CRS

bbox_gs = bbox_gdf.to_crs("EPSG:2154")

bbox_gs.geometry.values[0]

Horizontal rectangle cropping

When we changed the CRS of the bounding box, the shape of the bounding box became distorted, and it is no longer an horizontal rectangle. In order to crop the raster file to a horizontal rectangle, we need to define a new bounding box that is an horizontal rectangle in the projected CRS. To do this, we extract the x and y coordinates of the previous bounding box using the exterior.xy attribute of the Shapely geometry object and try to find the largest horizontal rectangle contained in this quadrilateral.

We then create a new Shapely Polygon object from these four corner points. This new polygon represents the horizontal rectangle that we will use to crop the raster file.

xx, yy = bbox_gs.geometry.values[0].exterior.xy

xx = np.sort(np.unique(xx))

x_min, x_max = xx[1], xx[-2]

yy = np.sort(np.unique(yy))

y_min, y_max = yy[1], yy[-2]

bbox = (x_min, y_min, x_max, y_max)

# Define points to create a polygon

point1 = (bbox[0], bbox[1])

point2 = (bbox[0], bbox[3])

point3 = (bbox[2], bbox[3])

point4 = (bbox[2], bbox[1])

# Create a polygon from the points

polygon_lam93 = Polygon([point1, point2, point3, point4])

polygon_lam93

Load, crop and saved the cropped raster

The mask() function from rasterio is used to crop the input raster to the specified polygon, resulting in a cropped raster that covers only the area of interest.

input_raster = rio.open(INPUT_DTM_FP)

# Crop the raster to the bounding box

out_image, out_transform = mask(input_raster, [polygon_lam93], crop=True, filled=False)

out_meta = input_raster.meta

out_meta.update(

{

"driver": "GTiff",

"height": out_image.shape[1],

"width": out_image.shape[2],

"transform": out_transform,

}

)

# Save the cropped raster to a new GeoTIFF file

with rio.open(CROPPED_DTM_FP, "w", **out_meta) as dest:

dest.write(out_image)

Enrich with RichDEM

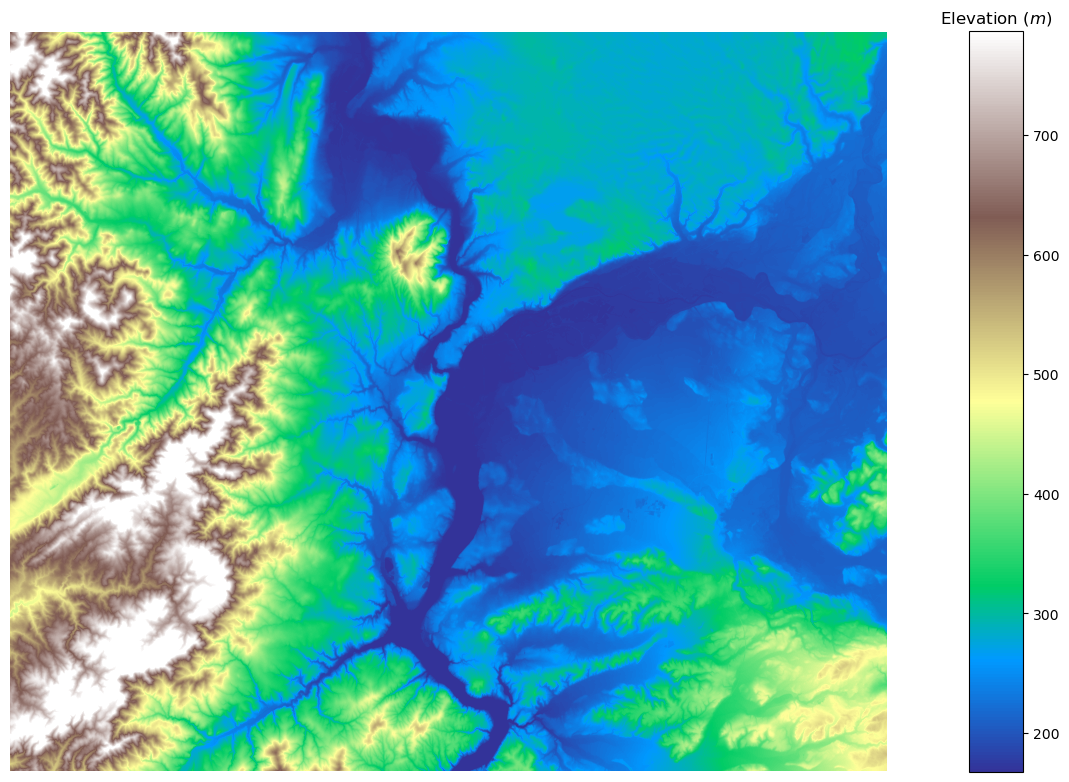

In this section, we start by loading the cropped DTM into RichDEM using the rd.LoadGDAL() function. We then use the rd.TerrainAttribute() function to calculate the slope and aspect of the terrain. Slope is a measure of the steepness of the terrain, while aspect is a measure of the direction that the slope is facing.

%%time

elevation = rd.LoadGDAL(CROPPED_DTM_FP)

CPU times: user 28.4 ms, sys: 247 ms, total: 275 ms

Wall time: 275 ms

_ = rd.rdShow(elevation, axes=False, cmap="terrain", show=False, figsize=FIGSIZE)

fig = plt.gcf()

ax = fig.gca()

_ = ax.set_title("Elevation ($m$)")

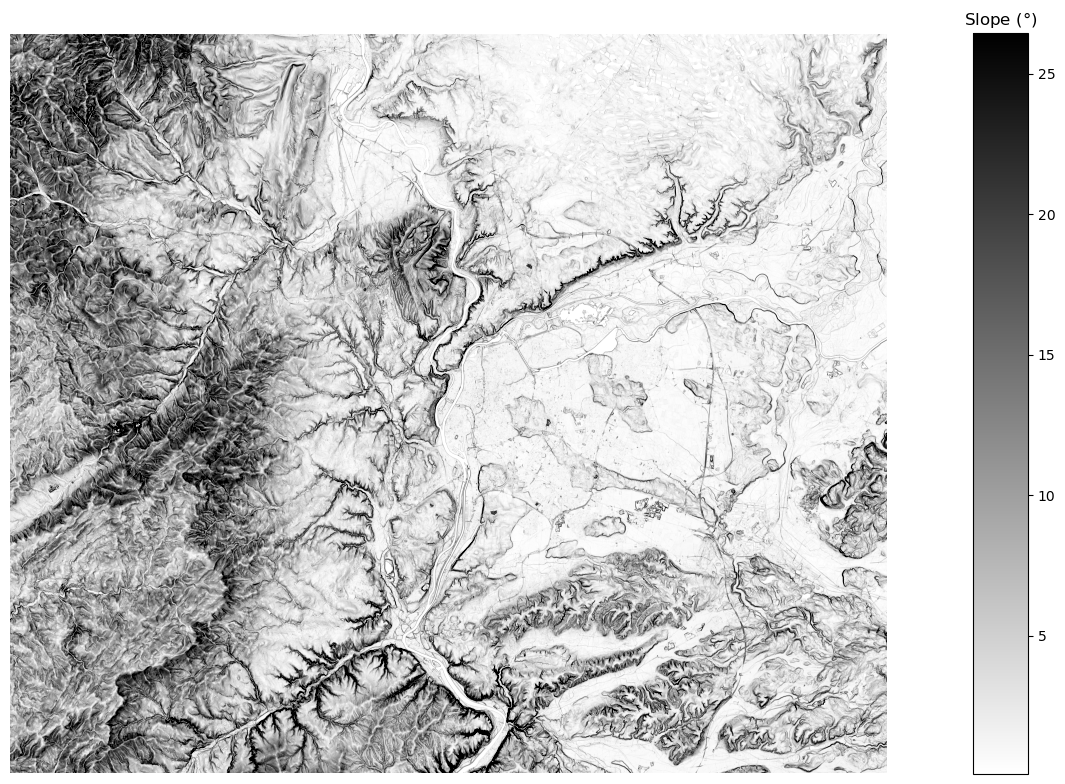

Slope

The slope calculation is performed using the method described by Berthold K.P. Horn [1], which calculates the slope in degrees based on the change in elevation between neighboring cells.

%%time

slope = rd.TerrainAttribute(elevation, attrib="slope_degrees")

CPU times: user 2.39 s, sys: 99.5 ms, total: 2.49 s

Wall time: 2.46 s

A Slope calculation (degrees)[39m

C Horn, B.K.P., 1981. Hill shading and the reflectance map. Proceedings of the IEEE 69, 14–47. doi:10.1109/PROC.1981.11918[39m

[2Kt Wall-time = 2.34489[39m ] (12% - 17.0s - 1 threads) ] (26% - 5.6s - 1 threads)

_ = rd.rdShow(slope, axes=False, cmap="binary", show=False, figsize=FIGSIZE)

fig = plt.gcf()

ax = fig.gca()

_ = ax.set_title("Slope ($°$)")

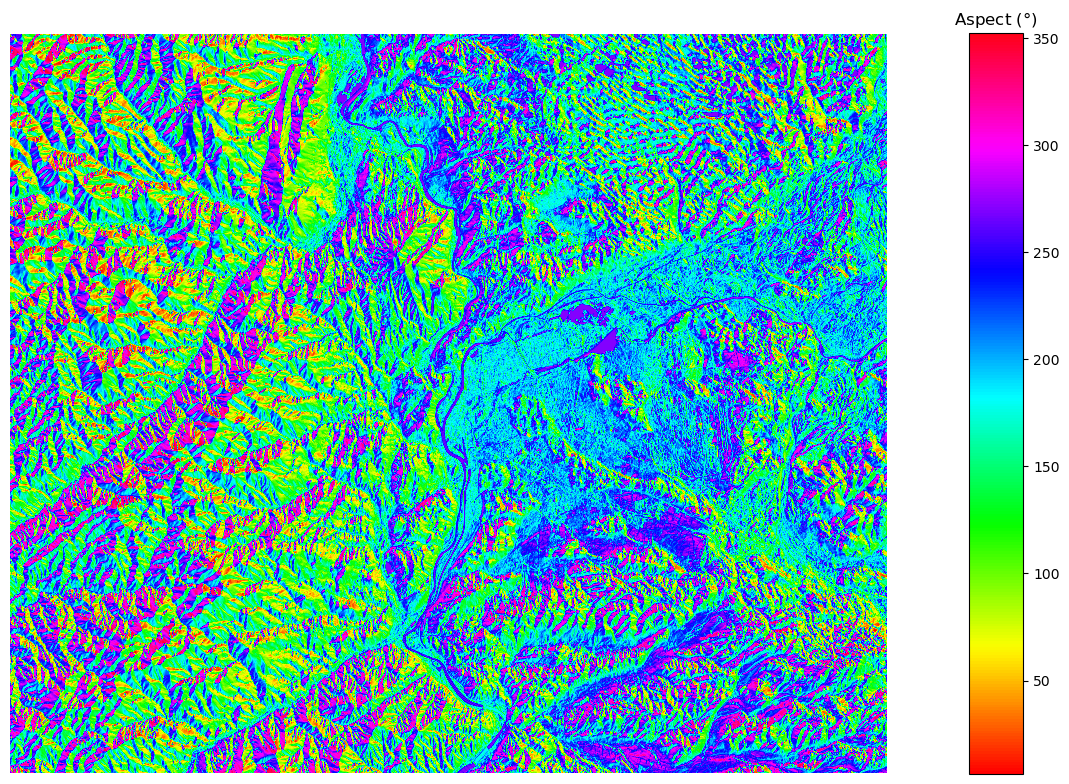

Aspect

The aspect calculation is also based on the method described by Berthold K.P. Horn [1], which calculates the aspect as the direction of the maximum rate of change of elevation.

%%time

aspect = rd.TerrainAttribute(elevation, attrib="aspect")

CPU times: user 4.35 s, sys: 122 ms, total: 4.47 s

Wall time: 4.39 s

A Aspect attribute calculation[39m

C Horn, B.K.P., 1981. Hill shading and the reflectance map. Proceedings of the IEEE 69, 14–47. doi:10.1109/PROC.1981.11918[39m

[2Kt Wall-time = 4.27062[39m ] (12% - 31.0s - 1 threads)

_ = rd.rdShow(

aspect, axes=False, cmap="hsv", show=False, figsize=FIGSIZE

) # cyclic colormap

fig = plt.gcf()

ax = fig.gca()

_ = ax.set_title("Aspect ($°$)")

In the aspect plot, the azimuth angle represents the direction of the slope. The aspect values are typically represented in degrees clockwise from north (0°):

- 0°-360°: North. This means that the slope is facing towards the north. In other words, if you were to stand on the slope and face downhill, you would be facing north. Since 0° and 360° are equivalent, both values represent north.

- 90°: East.

- 180°: South.

- 270°: West.

In the aspect plot, the colors represent the different azimuth angles.

Note that we could also compute some curvature data with the RichDEM package.

Save the enriched DTM

In the following we save the enriched DTM by writing the elevation, slope, and aspect bands to a new GeoTIFF file using the rasterio library.

# Read metadata of first file

dtm = rio.open(CROPPED_DTM_FP)

meta = dtm.meta

bands = [elevation, slope, aspect]

# Update meta to reflect the number of layers

meta.update(count=len(bands))

# Read each layer and write it to stack

with rio.open(OUTPUT_DTM_FP, "w", **meta) as dst:

for id, layer in enumerate(bands, start=1):

dst.write_band(id, layer)

Query the enriched DTM

Here we use random coordinates, generated within the bounding box of the enriched DTM in order to show a query example. We query elevation, slope, and aspect values at those points using the sample() method from the rasterio library. The resulting data is stored in a pandas DataFrame.

rng = np.random.default_rng(421)

# Set the number of random coordinates you want

num_points = 1000

# Generate random x, y coordinates within the bounding box

random_x = rng.uniform(dtm.bounds.left, dtm.bounds.right, num_points)

random_y = rng.uniform(dtm.bounds.bottom, dtm.bounds.top, num_points)

point_coords = list(zip(random_x, random_y))

point_df = pd.DataFrame(data={"x_2154": random_x, "y_2154": random_y})

%%time

dtm = rio.open(OUTPUT_DTM_FP)

point_df[["elevation", "slope", "aspect"]] = [x for x in dtm.sample(point_coords)]

CPU times: user 36.6 ms, sys: 23.6 ms, total: 60.1 ms

Wall time: 59.9 ms

point_df

| x_2154 | y_2154 | elevation | slope | aspect | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 820891.261579 | 6.538451e+06 | 383.420013 | 4.896277 | 309.077728 |

| 1 | 822310.025385 | 6.512176e+06 | 794.710022 | 23.744192 | 39.280010 |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 998 | 839788.130515 | 6.539853e+06 | 226.509995 | 4.520816 | 321.934448 |

| 999 | 839614.164818 | 6.499597e+06 | 158.139999 | 0.551047 | 117.900581 |

1000 rows × 5 columns

Hill shade visualization

In the final section of this blog post, we will explore how to create hillshade visualizations of the enriched DTM using the hillshade() function from the earthpy.spatial module. Hillshading is a technique used to create a shaded relief map that gives the illusion of three-dimensional depth to a two-dimensional surface. I discoved this module thanks to a post from Nicolas Mondon, a data journalist who creates some great content.

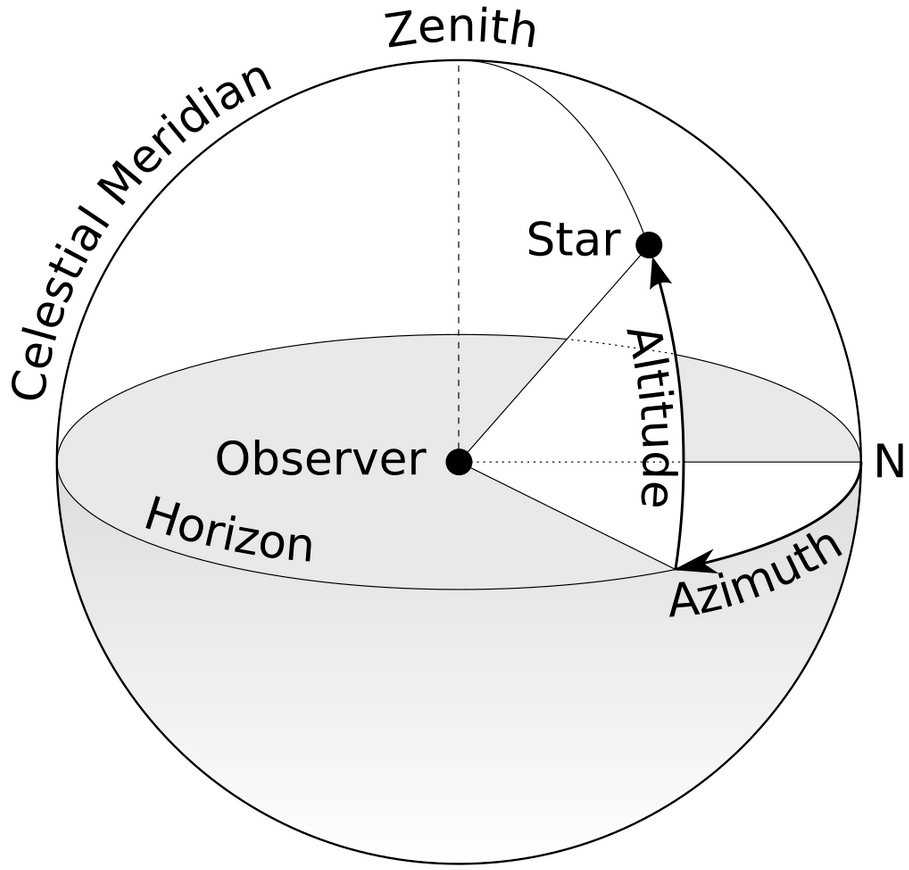

The hillshade() function takes three arguments: the elevation raster, the azimuth angle, and the altitude angle.

Source : wikipedia CC BY-SA 3.0

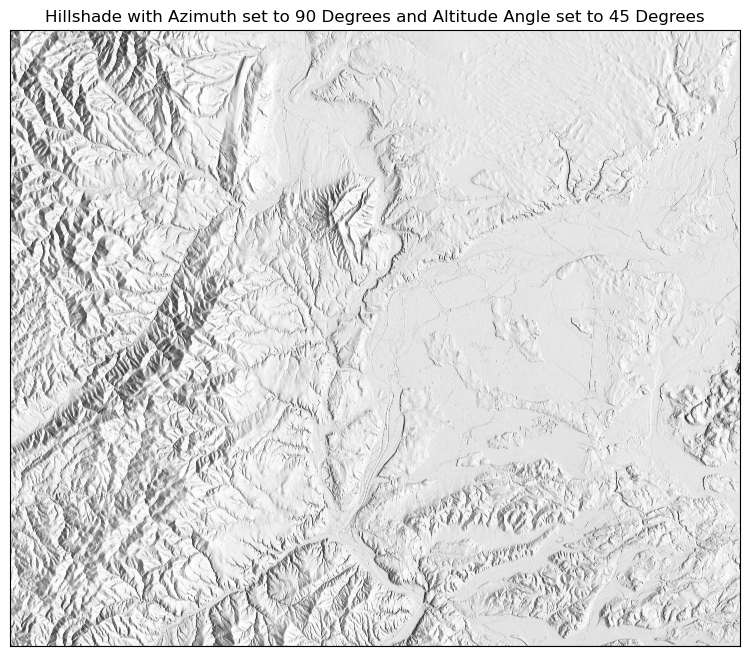

In the first example, we set the azimuth angle to 90 degrees and the altitude angle to 45 degrees.

azimuth = 90

altitude = 45

hillshade = es.hillshade(elevation, azimuth=azimuth, altitude=altitude)

# Plot the hillshade layer with the specified azimuth and altitude

_ = ep.plot_bands(

hillshade,

cbar=False,

title=f"Hillshade with Azimuth set to {azimuth} Degrees and Altitude Angle set to {altitude} Degrees",

figsize=FIGSIZE,

)

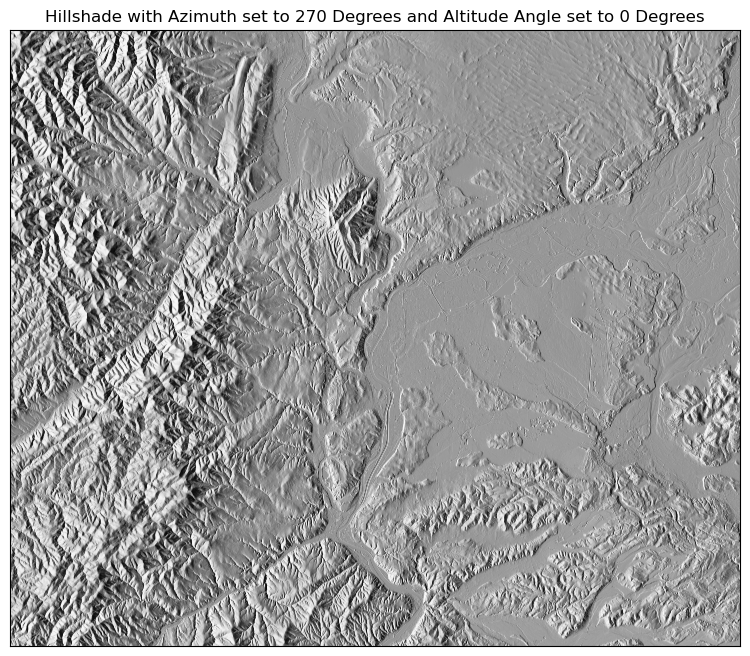

In the second example, we set the azimuth angle to 270 degrees and the altitude angle to 0 degrees.

azimuth = 270

altitude = 0

hillshade = es.hillshade(elevation, azimuth=azimuth, altitude=altitude)

# Plot the hillshade layer with the specified azimuth and altitude

_ = ep.plot_bands(

hillshade,

cbar=False,

title=f"Hillshade with Azimuth set to {azimuth} Degrees and Altitude Angle set to {altitude} Degrees",

figsize=FIGSIZE,

)

Reference

[1] Horn, B. K. P., “Hill shading and the reflectance map”, IEEE Proceedings, vol. 69, IEEE, pp. 14–47, 1981.